Southern Belize Offers Seaside Jungle Paradise

Note: Jaguar Reef was spared devastation, but check with Exernal Affairs before traveling. See our press release: Hurricane Mitch Never Happened in Belize (end of page three).

In the Belizean village of Hopkins, population 700, Western luxuries are as rare as the tourists. Homes are ramshackle huts, children play barefoot in dusty streets, and yards overgrown with jungle vines, and dinner depends much on the day’s catch or harvest.

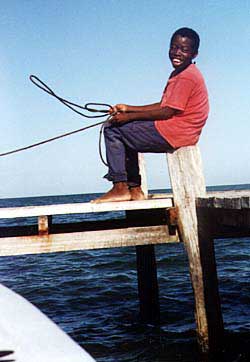

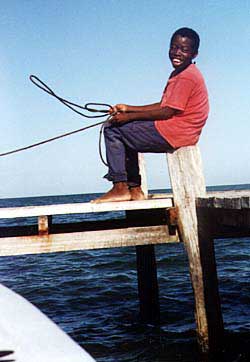

Chickens squawked and scattered as we rode rented bikes into town from nearby Jaguar Reef Resort. We turned onto a side street, where a lanky teenager in dreadlocks, blocked our path.

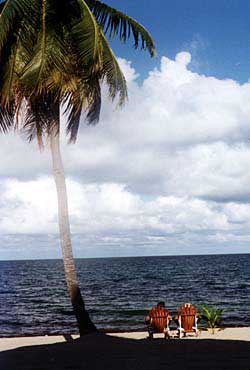

"Hey, my name’s Cliff," he grinned. "Welcome to paradise."

He said it without irony and with total accuracy. Just a few feet away, the warm Caribbean licked at bright ivory sand. Behind us, lush verdant jungle swallowed all but the highest peaks of the Maya Mountains.

Unlike most tourists, who flock to Belize’s northern coast to fish or dive, we opted for southern Belize, an intoxicating melange of virgin seacoast, untouched rainforest and primitive villages. About the size of Massachusetts, Belize was once home to more than one-million Mayans. Today, it contains barely 200,000 residents. Eighty percent of its rainforest remains under government protection, much of it unexplored.

Unlike most tourists, who flock to Belize’s northern coast to fish or dive, we opted for southern Belize, an intoxicating melange of virgin seacoast, untouched rainforest and primitive villages. About the size of Massachusetts, Belize was once home to more than one-million Mayans. Today, it contains barely 200,000 residents. Eighty percent of its rainforest remains under government protection, much of it unexplored.

We’d arrived in this Central American paradise a week earlier, connecting through Miami and Belize City. From there, an eight-passenger Maya Airways plane carried us to Dangriga, a fishing settlement where a landing strip had been carved from the jungle and ended abruptly in the Caribbean. The plane rolled to a stop at Rodney’s Place and Taxi, a shack that serves as passenger terminal, snackbar, control tower and taxi stop. A worker from a local inn greeted two guests, loaded their luggage into a wheelbarrow and led a procession into town, a dozen dogs yapping at their heels.

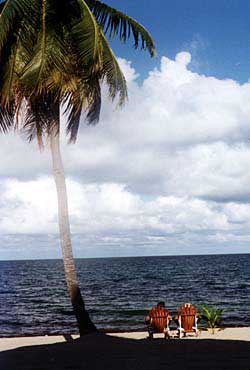

It was just a short ride to Jaguar Reef Resort, nestled on a remote stretch of Caribbean beach. Our room was just above the high-water line, and each night we fell asleep to the rhythm of the sea. Each morning we woke early to watch the sun burst over the azure horizon.

It was just a short ride to Jaguar Reef Resort, nestled on a remote stretch of Caribbean beach. Our room was just above the high-water line, and each night we fell asleep to the rhythm of the sea. Each morning we woke early to watch the sun burst over the azure horizon.

A popular Belizean bumper sticker reads "No Shirt, No Shoes, No Problem," and that policy stands at Jaguar Reef. Each morning, we kicked through the sand to a tiled patio, where we enjoyed eggs or breakfast tortillas and an endless juice supply from just-picked fruit. At night, we dined in starlight.

Jaguar Reef offers its guests free use of bicycles and kayaks, and we used both to explore the coast. The resort is new, and tourists are still a novelty in the region. Wherever we biked, adults smiled and children waved. On our return from exploring the ruins of an old sugar mill, we stopped at a small shop for sodas, where owner Isaac Kelly joined us on the patio. The people of Belize are remarkably radiant in their happiness, their graciousness, and their extreme pride in their country, and Kelly was no different. His greatest pride, perhaps, is in the peaceful relations between the country’s many ethnic groups. "Just up the road, there’s a Mayan village," he said. "Here in Hopkins, we have Garifuna (descendants of Black Caribe Indians). In between, there’s Creoles and Mestizos. We all get along."

Jaguar Reef offers its guests free use of bicycles and kayaks, and we used both to explore the coast. The resort is new, and tourists are still a novelty in the region. Wherever we biked, adults smiled and children waved. On our return from exploring the ruins of an old sugar mill, we stopped at a small shop for sodas, where owner Isaac Kelly joined us on the patio. The people of Belize are remarkably radiant in their happiness, their graciousness, and their extreme pride in their country, and Kelly was no different. His greatest pride, perhaps, is in the peaceful relations between the country’s many ethnic groups. "Just up the road, there’s a Mayan village," he said. "Here in Hopkins, we have Garifuna (descendants of Black Caribe Indians). In between, there’s Creoles and Mestizos. We all get along."

We doubled back into Hopkins to hang out -- literally -- at the Swinging Armadillo, a local bar balanced on stilts over the sea. We lay in hammocks, sipping fresh fruit juice and watching men paddle their small skiffs toward shore and unload the day’s catch. We shared the porch with one other guest, a ponytailed young Canadian who napped blissfully between chapters of D.H. Lawrence.

Kayaking proved an excellent means of seeking out wildlife among the mangroves that spread their tangled roots into the sea. Stokey, the resort’s resident retriever, chased along the beach after us, then paddled through the waves to join us. Exhausted, he hitched a ride back on a kayak.

Belize boasts the world’s second largest barrier reef, a boon for divers and snorkelers as well as for coastal residents who enjoy the hurricane buffer the reef provides. We spent a day snorkeling over part of the reef, the resort’s dive boat carrying us to islands so small no map charts them. Our skipper beached the boat on a milky-white sandbar between two tiny cayes lined with coconut trees. The Caribbean had never looked so idyllic, and we wondered, as we lay in the gentle aquamarine shallows, how much better life could get.

Still, what had brought us to Jaguar Reef was its proximity to the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Preserve. There, in the realm of the world’s highest concentration of jaguars, we would spend two days hiking, camping and tracking the elusive cats.

The resort provided tents, sleeping bags, food and cooking gear, and our guide, Raul, briefed us on what to pack and wear. As we set up camp, Raul pointed out that only one other visitor was in the 100,000-acre preserve that day. "We pretty much have the whole park to ourselves," he said.

An archaeologist by training, Raul had spent months in Belize’s jungles. He explained the tracks we saw and what they meant. A rutted path coming from crushed underbrush usually meant a pack of peccaries -- a kind of wild pig. The small paw-prints of ocelots. The hoofed tracks of the tapir -- or mountain cow. He squatted at a v-shaped print of a white-tail deer, which usually meant jaguars were nearby, contemplating dinner. Sure enough, he soon pointed out a fresh pair of cat tracks -- a mother and its cub. On our return, we saw fresh tracks over ours: a large jaguar.

"We may not see them, but they’re here, and they know we’re here," he said.

While we saw nothing more of the larger beasts than their prints, we did enjoy a visual feast of cattle egrets, hummingbirds, toucans, woodpeckers andgrackles. A wolf spider stared back from its nighttime lair with glaring red eyes. When we curiously poked a twig into a small hole, an indignant tarantula grabbed it violently and stalked out to investigate. Thankfully, none of the park’s poisonous snakes crossed our path. We weren’t as lucky with the countless mosquitoes that proved impervious to the strongest repellent..

Also preserved in the Basin is a staggering array of plant life that, though often menacing and bizarre, makes for fascinating hikes. With a single swipe of his machete, Raul offered us a refreshing drink from a water vine. He warned us about a tree whose razor-sharp thorns inject a potent toxin into the blood. The only known cure is the tree’s own sap. Hence its name: the give-and-take tree.

Also preserved in the Basin is a staggering array of plant life that, though often menacing and bizarre, makes for fascinating hikes. With a single swipe of his machete, Raul offered us a refreshing drink from a water vine. He warned us about a tree whose razor-sharp thorns inject a potent toxin into the blood. The only known cure is the tree’s own sap. Hence its name: the give-and-take tree.

On a seven-hour hike up the Outlier Trail, we forded streams, clambered over rocks, and slogged through undergrowth. A false step often tossed us several feet back into oozing mud. Finally, we crested the summit and viewed the entire park, including Victoria Peak ( believed to be the highest point in Belize, but maps issue the caveat that the country hasn’t been fully explored).

Inner-tubes borrowed from the park ranger allowed us to cool off on a leisurely half-hour drift down the Sittee River. After we dried off, Eugene asked if we’d like to join him on a new trail still being cut up a high bluff. He led the way, slashing nearly constantly with his machete. We reached the top and were filled with awe and honor when he announced we were the first non-Mayans ever to reach that spot.

We bedded down early that night, greedy for sleep, despite feeling that the entire jaguar population was making dinner plans. At dawn we awoke to a staccato grunting, almost like a drumming. Soon, more grunts joined in until it became a throaty chorus. "Howler monkeys," Raul said. "First the leader states his dominance, then the others agree and claim the clan’s territory."

We bedded down early that night, greedy for sleep, despite feeling that the entire jaguar population was making dinner plans. At dawn we awoke to a staccato grunting, almost like a drumming. Soon, more grunts joined in until it became a throaty chorus. "Howler monkeys," Raul said. "First the leader states his dominance, then the others agree and claim the clan’s territory."

That night, our last, the moon rose perfectly between two palm trees as we dined on Jaguar Reef’s patio. We knew it would be difficult leaving Belize, its warm and hardy people, its lush landscape and its love for its precious environment. We also knew that, unlike in many neighboring countries, this paradise wouldn’t be lost.

If You Go:

Belize has become a mecca for eco-travelers and tourists in search of "soft" adventure. Most tour operators concentrate either on the popular dive areas in the north or on specific activities, like scuba diving, bone fishing or coastal kayaking. After considerable research, we chose Capricorn Leisure Corp. (800-426-6544), which once served as Belize’s tourism bureau in the U.S. With extensive contacts through the country, Capricorn put together a custom package for us focusing mostly on the country’s less-traveled regions.

Getting There

Getting There

American Airlines offers daily air service to Belize City through Miami. Small Maya Airlines planes fly regularly between Belize City and Dangriga.

Lodging

Much of Belize is still a bargain. Expect to pay as much as $60 per night per person, including meals, in a bungalow at one of Belize’s "micro-resorts" like Jaguar Reef Resort (General Delivery, Hopkins, Stann Creek District; 011-501-212041). You can also spend as little as $10 per person for a thatch hut on a farm.

Getting Around

Car rentals are available, but roads are rugged and poorly marked. It’s best to choose lodging that also offers airport pick-up and guide service.

Language

The official language is English, although you’re likely to hear Spanish, Creole, Mayan and Garifuna (Black Caribe Indian) spoken.

Weather

With a sub-tropical climate, Belize’s temperature averages 79 degrees but can range from 50-95 degrees. The dry season is November-May, the rainy season (with up to 15 feet of rainfall in the south) June-November.

Food

Food ranges from basic beans and rice to exotic international. Most hotels and restaurants make use of abundant local fresh produce and meats. Water is safe to drink in most locations.

Clothing

Informality is the norm. Although the tendency is to dress for temperature, long-sleeve shirts and long pants provide better protection against the sun and the almost ever-present mosquitoes.

Health

No vaccinations are required, but travelers to jungle areas should consider anti-malaria measures. Despite generally good water quality and food preparation, tourists should check with their physicians about ways to deal with travelers’ diarrhea and related ailments.

For visitor information contact the Belize Tourist Board, 83 North Front Street, Belize City, Belize, Tel. 1-800-624-0686 Fax: 011-501-2-77490. E-mail: btbb@btl.net; Internet: www.belizenet.com

About Mitch from Belize tourism...

Hurricane Mitch Never Happened in Belize

Belize City, Belize.

Once a year at the beginning of each hurricane season, a candlelight vigil of over 1000 people march from church to church in Belize City. This pilgrimage to the Lady of Guadeloupe, protector from storms, has occurred each year since Hurricane Hattie devastated Belize on October 31, 1961. Perhaps this sacred remembrance can help to explain the strange storm pattern of Hurricane Mitch, which nearly circled completely around Belize without harming the country.

Forecasting predicted that Hurricane Mitch would head straight for the Belize coast. Evacuation warnings and preparations for the storm began as early as Sunday, October 25th. By Monday Belize's Hummingbird and Western Highways were bumper to bumper with traffic as low-lying and coastal residents headed forprotection in the Maya Mountains. Cayo District became the area of mass exodus and was prepared with food, shelter and clothing. Evacuees sought safety with friends and relatives and in hotels and government shelters. Tourists were urged to return home.

Hurricane Mitch posed threat to the coastal areas and offshore cayes with predicted tidal surges of up to 25 feet. If Hurricane Mitch had hit Belize, winds would have blown the palapa and zinc roofs off many of the buildings in coastal areas and rivers could have risen as much as 50 feet to flood towns in the highland areas -- BUT NONE OF THAT HAPPENED.

Mitch steered clear of Belize. Its winds never even reached the cayes and the storm rains never pelted the towns. Hurricane Mitch never happened in Belize.

Friday, October 30, 1998, refugees returned to their coastal and seaside homes. Debris had washed ashore and dive piers along the offshore cayes were buckled or lost to the waves. These were the only casualties from the storm. A tremendous amount of white sand was left on the beaches of Ambergris Caye, so raking the new beach out became top priority, as was removing any planks washed ashore from the piers. The interior suffered no damage.

The Maya Mountains of Belize are made of limestone karst with only a thin layer of topsoil supporting the forest, so mudslides were never a concern. Rivers were inspected by the National Health Advisors and suffered no contamination as flooding was minimal. Belize rapidly returned to normal. Piers on the cayes are nearly rebuilt, postponed Halloween parties were thrown and when concerned friends and visitors inquire about the country, Belize's relieved residents happily inform them that there was "No Mitch in Belize."

English-speaking Belize offers a unique vacation experience -- visitors may combine diving, boating and fishing with exploring Belize's rain forests, wildlife reserves and, archaeological sites while sharing in the colorful, diverse culture of its people.

Belize boasts the world’s second largest barrier reef, a boon for divers and snorkelers as well as for coastal residents who enjoy the hurricane buffer the reef provides. We spent a day snorkeling over part of the reef, the resort’s dive boat carrying us to islands so small no map charts them. Our skipper beached the boat on a milky-white sandbar between two tiny cayes lined with coconut trees. The Caribbean had never looked so idyllic, and we wondered, as we lay in the gentle aquamarine shallows, how much better life could get.Still, what had brought us to Jaguar Reef was its proximity to the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Preserve. There, in the realm of the world’s highest concentration of jaguars, we would spend two days hiking, camping and tracking the elusive cats.

The resort provided tents, sleeping bags, food and cooking gear, and our guide, Raul, briefed us on what to pack and wear. As we set up camp, Raul pointed out that only one other visitor was in the 100,000-acre preserve that day. "We pretty much have the whole park to ourselves," he said.

An archaeologist by training, Raul had spent months in Belize’s jungles. He explained the tracks we saw and what they meant. A rutted path coming from crushed underbrush usually meant a pack of peccaries -- a kind of wild pig. The small paw-prints of ocelots. The hoofed tracks of the tapir -- or mountain cow. He squatted at a v-shaped print of a white-tail deer, which usually meant jaguars were nearby, contemplating dinner. Sure enough, he soon pointed out a fresh pair of cat tracks -- a mother and its cub. On our return, we saw fresh tracks over ours: a large jaguar.

"We may not see them, but they’re here, and they know we’re here," he said.

While we saw nothing more of the larger beasts than their prints, we did enjoy a visual feast of cattle egrets, hummingbirds, toucans, woodpeckers andgrackles. A wolf spider stared back from its nighttime lair with glaring red eyes. When we curiously poked a twig into a small hole, an indignant tarantula grabbed it violently and stalked out to investigate. Thankfully, none of the park’s poisonous snakes crossed our path. We weren’t as lucky with the countless mosquitoes that proved impervious to the strongest repellent..

Also preserved in

the Basin is a staggering array of plant life that, though often menacing and bizarre,

makes for fascinating hikes. With a single swipe of his machete, Raul offered us a

refreshing drink from a water vine. He warned us about a tree whose razor-sharp thorns

inject a potent toxin into the blood. The only known cure is the tree’s own sap.

Hence its name: the give-and-take tree.

Also preserved in

the Basin is a staggering array of plant life that, though often menacing and bizarre,

makes for fascinating hikes. With a single swipe of his machete, Raul offered us a

refreshing drink from a water vine. He warned us about a tree whose razor-sharp thorns

inject a potent toxin into the blood. The only known cure is the tree’s own sap.

Hence its name: the give-and-take tree.

On a seven-hour hike up the Outlier Trail, we forded streams, clambered over rocks, and slogged through undergrowth. A false step often tossed us several feet back into oozing mud. Finally, we crested the summit and viewed the entire park, including Victoria Peak ( believed to be the highest point in Belize, but maps issue the caveat that the country hasn’t been fully explored).

Inner-tubes borrowed from the park ranger allowed us to cool off on a leisurely half-hour drift down the Sittee River. After we dried off, Eugene asked if we’d like to join him on a new trail still being cut up a high bluff. He led the way, slashing nearly constantly with his machete. We reached the top and were filled with awe and honor when he announced we were the first non-Mayans ever to reach that spot.

We bedded down

early that night, greedy for sleep, despite feeling that the entire jaguar population was

making dinner plans. At dawn we awoke to a staccato grunting, almost like a drumming.

Soon, more grunts joined in until it became a throaty chorus. "Howler monkeys,"

Raul said. "First the leader states his dominance, then the others agree and claim

the clan’s territory."

We bedded down

early that night, greedy for sleep, despite feeling that the entire jaguar population was

making dinner plans. At dawn we awoke to a staccato grunting, almost like a drumming.

Soon, more grunts joined in until it became a throaty chorus. "Howler monkeys,"

Raul said. "First the leader states his dominance, then the others agree and claim

the clan’s territory."

That night, our last, the moon rose perfectly between two palm trees as we dined on Jaguar Reef’s patio. We knew it would be difficult leaving Belize, its warm and hardy people, its lush landscape and its love for its precious environment. We also knew that, unlike in many neighboring countries, this paradise wouldn’t be lost.

If You Go:Belize has become a mecca for eco-travelers and tourists in search of "soft" adventure. Most tour operators concentrate either on the popular dive areas in the north or on specific activities, like scuba diving, bone fishing or coastal kayaking. After considerable research, we chose Capricorn Leisure Corp. (800-426-6544), which once served as Belize’s tourism bureau in the U.S. With extensive contacts through the country, Capricorn put together a custom package for us focusing mostly on the country’s less-traveled regions.

Getting

There

Getting

There

American Airlines offers daily air service to Belize City through Miami. Small Maya

Airlines planes fly regularly between Belize City and Dangriga.

Lodging

Much of Belize is still a bargain. Expect to pay as much as $60 per night per person,

including meals, in a bungalow at one of Belize’s "micro-resorts" like

Jaguar Reef Resort (General Delivery, Hopkins, Stann Creek District; 011-501-212041). You

can also spend as little as $10 per person for a thatch hut on a farm.

Getting Around

Car rentals are available, but roads are rugged and poorly marked. It’s best to

choose lodging that also offers airport pick-up and guide service.

Language

The official language is English, although you’re likely to hear Spanish, Creole,

Mayan and Garifuna (Black Caribe Indian) spoken.

Weather

With a sub-tropical climate, Belize’s temperature averages 79 degrees but can range

from 50-95 degrees. The dry season is November-May, the rainy season (with up to 15 feet

of rainfall in the south) June-November.

Food

Food ranges from basic beans and rice to exotic international. Most hotels and restaurants

make use of abundant local fresh produce and meats. Water is safe to drink in most

locations.

Clothing

Informality is the norm. Although the tendency is to dress for temperature, long-sleeve

shirts and long pants provide better protection against the sun and the almost

ever-present mosquitoes.

Health

No vaccinations are required, but travelers to jungle areas should consider anti-malaria

measures. Despite generally good water quality and food preparation, tourists should check

with their physicians about ways to deal with travelers’ diarrhea and related

ailments.

For visitor information contact the Belize Tourist Board, 83 North Front Street, Belize City, Belize, Tel. 1-800-624-0686 Fax: 011-501-2-77490. E-mail: btbb@btl.net; Internet: www.belizenet.com

About Mitch from Belize tourism...

Hurricane Mitch Never Happened in Belize

Belize City, Belize.

Once a year at the beginning of each hurricane season, a candlelight vigil of over 1000

people march from church to church in Belize City. This pilgrimage to the Lady of

Guadeloupe, protector from storms, has occurred each year since Hurricane Hattie

devastated Belize on October 31, 1961. Perhaps this sacred remembrance can help to explain

the strange storm pattern of Hurricane Mitch, which nearly circled completely around

Belize without harming the country.

Forecasting predicted that Hurricane Mitch would head straight for the Belize coast. Evacuation warnings and preparations for the storm began as early as Sunday, October 25th. By Monday Belize's Hummingbird and Western Highways were bumper to bumper with traffic as low-lying and coastal residents headed forprotection in the Maya Mountains. Cayo District became the area of mass exodus and was prepared with food, shelter and clothing. Evacuees sought safety with friends and relatives and in hotels and government shelters. Tourists were urged to return home.

Hurricane Mitch posed threat to the coastal areas and offshore cayes with predicted tidal surges of up to 25 feet. If Hurricane Mitch had hit Belize, winds would have blown the palapa and zinc roofs off many of the buildings in coastal areas and rivers could have risen as much as 50 feet to flood towns in the highland areas -- BUT NONE OF THAT HAPPENED.

Mitch steered clear of Belize. Its winds never even reached the cayes and the storm rains never pelted the towns. Hurricane Mitch never happened in Belize.

Friday, October 30, 1998, refugees returned to their coastal and seaside homes. Debris had washed ashore and dive piers along the offshore cayes were buckled or lost to the waves. These were the only casualties from the storm. A tremendous amount of white sand was left on the beaches of Ambergris Caye, so raking the new beach out became top priority, as was removing any planks washed ashore from the piers. The interior suffered no damage.

The Maya Mountains of Belize are made of limestone karst with only a thin layer of topsoil supporting the forest, so mudslides were never a concern. Rivers were inspected by the National Health Advisors and suffered no contamination as flooding was minimal. Belize rapidly returned to normal. Piers on the cayes are nearly rebuilt, postponed Halloween parties were thrown and when concerned friends and visitors inquire about the country, Belize's relieved residents happily inform them that there was "No Mitch in Belize."

English-speaking Belize offers a unique vacation experience -- visitors may combine diving, boating and fishing with exploring Belize's rain forests, wildlife reserves and, archaeological sites while sharing in the colorful, diverse culture of its people.

Famous Faces, Famous Places and Famous Foods

Famous Faces, Famous Places and Famous Foods